Michael Hoskin: interpreter of a prehistoric code written in stone and stars

Los trabajos del arqueoastrónomo Michael Hoskin han servido para sustentar el reconocimiento de la UNESCO

“See the giant!”, a father tells his son as he uses his finger to sketch the rocky formation overlooking Antequera (Málaga), which recalls a huge, imposing face that can be seen from afar. To look at them, it could be any father showing his son the silhouette of La Peña de Los Enamorados, or “the Indian”, as it is referred to by travellers passing by on the A92 highway. But here, the father is Michael Hoskin (London, 1930), the scientist whose work has led to this “giant”, the dolmens and the Karstic landscape of El Torcal receiving international recognition through their declaration as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Hoskin, a lecturer at the University of Cambridge, has demonstrated the uniqueness of this Antequera dolmen with all the knowledge and authority of a man who has studied more than 3,000 sites over the course of his life, many of which are collected in his book ‘Tombs, Temples and their Orientations. A New Perspective on Mediterranean Prehistory’ (2001). Menga may be the only dolmen in continental Europe and the Mediterranean that was not built with an orientation towards the sun or moon, instead facing the giant face of La Peña.

Like Hoskin, indeed like anybody, the inhabitants of the area in around 4000 BCE must have been so impressed by this great mass looking to the heavens that they decided to break with their traditional pattern of construction. How did the researcher reach this conclusion?

Vista de La Peña de los Enamorados. Autor: Javier Pérez González. Archivo del Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera.

Dolmens are collective tombs where Neolithic and Copper Age clans honoured their dead. Nonetheless, they go far beyond just being an architectural structure; according to Hoskin, they represent each society’s worldview. The structures were not built at random: they follow precise lines of orientation, implying knowledge of astronomy. Men and women would labour to build their burial chambers after the harvest was brought in, around the month of September. On the first day of the building work they would study the sky to align their monument with the sun or some other celestial object.

In this way, these prehistoric builders have passed on their worldview to the present day, coded in a language that would persist over time: the rock and the sky. Hoskin, as an archaeoastronomer, is the interpreter of this particular way of writing, used by the societies that looked to the sky from the beginning.

An adventure that began in Andalusia

When his brilliant scientific career ended with his retirement in 1988, Hoskin embarked on a daunting adventure: to measure and analyse the megalithic monuments of Western Europe, the Mediterranean and North Africa. As he told iDescubre, it all began when he was invited by a professor at the University of Granada, Margarita Orfila Pons, to whom he affectionately refers as Maiti, to visit Los Millares (near Almería) to analyse the tholoi, a type of circular tomb. “When we studied the orientations, we initially thought they might have been random. Then we realised they were all facing easterly. It was evident that the builders were required to follow a pattern when they started work on a new tomb.”

When they finished work in Los Millares, he and Maiti travelled to Montefrío in Granada, where there was a similar number of megalithic (stone) tombs. Hoskin explains that although these two societies were completely independent, the burial constructions of both were oriented approximately toward the same cardinal point. “How could this be? Identical patterns in two separate cultures and places. This mystery led me to explore Spain, Portugal and other parts of Europe, Mediterranean islands and North Africa,” he recalls.

For Hoskin, it is extraordinary that when farming societies throughout Europe learned agriculture and settled permanently in one place, they should all decide to erect collective tombs for their deceased, and that they should all follow a pattern in the orientations they adopted for these tombs. “It’s simply astonishing. It’s as though they’d used mobile phones, organised a video conference and said ‘What shall we do? Let’s make communal tombs’,” he explains.

As well as selecting constructions for their collective burials, prehistoric clans used the sky to dictate the orientations of the tombs. In the book El Centro Solar Michael Hoskin (“The Michael Hoskin Solar Centre”) the researcher describes the analytical process that archaeoastronomers follow. The process begins with locating dolmens of a particular type, then measuring their orientation, the imaginary view of the sky for bodies looking out through the entrance of the tomb from within. Next, they examine whether these directions follow any pattern. If they find one, the scientists look at whether the objective is in the sky or on Earth. If the sky determines the orientation of the structures, the objective may be the sunrise or sunset at some time of the year, or the points where the moon or a particular star rises or sets at a given time of year.

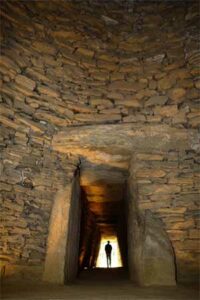

Interior dolmen de Menga. Autor: Javier Pérez González. Archivo del Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera.

Following this methodology and having taken measurements in various different countries, Hoskin eventually arrived in Antequera, where he met a challenge. “My first visit to these dolmens was a landmark in my work,” he says.

Each of the three dolmens at the Antequera site is unique within its category in the immediate area, making it impossible to establish a pattern of orientation. “The Menga dolmen faces north-east, further north than the sun is ever seen, and towards the Peña de los Enamorados. This is the only example of the 3,000 I know whose objective is on the Earth, not in the sky,” the researcher points out. Having studied such a vast number of structures enabled the archaeoastronomer to recognise that the orientation of the dolmen was unique: for somebody who knows the patterns of such a distinctive language, it is simple to recognise elements that are out of the ordinary.

Asked if the dolmen’s builders would have been aware of their innovation, Hoskin jokes that we should go back and ask them, adding that “Personally, I think they would have been. La Peña has been considered a sacred site throughout history.”

Viera and El Romeral

El Romeral. Autor: Miguel Ángel Blanco de la Rubia . Archivo del Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera.

Beside the Menga tomb, which looks out upon that giant stargazer instead of itself facing the sky, is another construction, the Viera dolmen. Hoskin stresses that while the Viera dolmen’s orientation is typical (it faces the sun at the March and September equinoxes), its design of construction is rarely seen.

Somewhat removed from the other two is El Romeral, a massive beehive-like structure to which there are only 3 or 4 comparable tombs in Spain and Portugal. “What’s extraordinary about El Romeral is that tholoi are made up of small stones that could collapse. However, it is in perfect condition,” he points out.

The dome of El Romeral and the chamber of the Menga tomb are some of the largest interior spaces in the world. “They are enormous in size,” says Hoskin. The orientation, size, diversity and interaction with natural objects like La Peña and El Torcal were the arguments for declaring them a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Feeling the dolmens

For Hoskin, UNESCO simply endorsed what he had already felt when he visited the Antequera site for the first time and on his many subsequent visits: its unique character. That is why he decided in April to bring 25 family members – four generations – to witness his proudest discovery. “You have to see it to believe it. The Egyptian pyramids are nothing compared to the dolmens,” he says.

During the tour of the site, Hoskin shared his passion for the structures with his own clan. “I thought it might be an opportunity for them to see these dolmens and understand why I’ve spent so much time measuring them. They’re seeing the meaning of a part of my life. If you spend time at the dolmens, you can feel them, understand them,” he says.

This understanding and investigation make Hoskin an exceptional interpreter of these sites. He receives the legacy and the message of the prehistoric inhabitants of the area and leaves his own in the present day. One way Hoskin has made his mark is the photographic archive he donated to Andalusia in 2011, deposited at the Archaeological Ensemble of the Antequera Dolmens archive. The collection contains 5,466 photographs of megaliths from North Africa, western Europe and several Mediterranean islands. Together with this, he also offered part of his library, with 107 scientific publications. These donations further show the scientist’s enthusiasm for sharing and disseminating his knowledge.

His message comes across as a reflection: the collaborative work of men and women during the construction of Menga. This would have become the common purpose of the entire clan over many years. For Hoskin, it is difficult to achieve this extraordinary cooperation in the present day, which is why he offers to teach today’s societies about the societies of the past.

This interpreter of Neolithic societies’ terrestrial and cosmic code shows the legacy they left to their present-day descendants, and to all humankind. A universal inheritance written in stone and stars.

Homages in the “city of the sun”

“Let the sun rise from Antequera,” goes a local proverb. The city is linked to the sun not only through spoken tradition or the title of El Sol de Antequera, its longest-running newspaper; it also takes centre stage at a solar centre dedicated to Michael Hoskin. This takes the form of an esplanade that receives visitors to the site of the dolmens and provides information to assist understanding the concept of sun orientation that can be seen there.

Since April, another space in the “City of the Sun”, as Antequera is known, bears the scientist’s name. Hoskin’s curious eyes keep discovering the city’s winding streets as he arrives at Arco de los Gigantes, where a new lookout point has been christened in his honour. “I’ve seen parts of Antequera that I didn’t know before and I didn’t expect to be so charming,” the scientist says on the way to the inauguration. The new square is presided over by a bust of Hoskin, looking out towards the “giant”, which, like the builders of the Menga dolmen, the scientist always has in mind when he visits the city. “I’ve only seen it from a distance, but I am always aware that it’s there,” he says.

His grandson Sam Hoskin didn’t hesitate to immortalise the sculpture with a photo, tweeting: “Not every day a bust of your grandpa is put up #Antequera #Dolmen”.

During the trip to Antequera, which he considers his second home, Hoskin also received the Menga Medal, a bronze piece portraying the city’s mythical foundation by Hercules. According to legend, the dolmen is material evidence of one of the Greek hero’s labours in the westernmost corner of the Mediterranean.

Charles V’s chronicler Florián de Ocampo described the event as follows: “[…] Hercules came came from the mountain, and to memorialise the magnificent action he had just performed, he drove twenty-five large stones into the ground, then drove three more into the centre, as pillars. Then he covered the area with five enormous slabs… When Hercules departed to continue his pursuit of the sons of Geryon, he left settlers behind: this is how Antikaria was founded.”

Science for global recognition

Dolmen de Menga. Autor: Javier Pérez González. Archivo del Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera.

Science has supported the worldwide dissemination of Antequera’s legacy. On 15 July 2016 at the 40th session of the World Heritage Committee in Istanbul, the Antequera Dolmens Site was awarded UNESCO World Heritage status. The declaration gives three justifications for the site’s Outstanding Universal Value. Firstly, the colossal size of the megaliths; secondly, the intimate interaction of the megalithic monuments with nature; and finally, the fact that the three tombs, with their unique designs and their technical and formal differences, are evidence of the coexistence of the two great megalithic architectural traditions of the Iberian Peninsula.

A team of scientists argued for this definition of Outstanding Universal Value. Researchers from the universities of Cádiz, Granada, Jaén, Málaga, Seville, Alcalá de Henares, La Laguna, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, the Spanish National University of Distance Education (UNED), Pompeu Fabra, Cambridge, Southampton and Tübingen participated in the project.

However, the most distinguished name from all of these institutions is Michael Hoskin’s. His research in Europe and Africa laid the foundations for the criterion of the singular conception of Antequera’s megalithic landscape, born of an original interrelation between cultural and natural monuments.

Dolmen de Menga. Autor: Juan Rodríguez Bravo. Archivo del Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera.

Despite his contribution, Hoskin is very modest and stresses that he only played a small part, highlighting the work of the director of the Archaeological Ensemble of the Antequera Dolmens, Bartolomé Ruiz, a close friend of his: although he does not remember the exact moment when he discovered the unique orientation of the Menga dolmen, he thinks the two may have been having a drink together. “Antequera is the home of the biggest smile I know, Bartolomé’s, as well as to the biggest dolmens in Europe, which to everyone’s joy have been declared World Heritage. Bartolomé worked tirelessly to achieve that,” he recalls.

Hoskin believes that this international recognition means more people will come to the city and appreciate the importance of the site. It will also protect the site, preventing any building work from damaging the surrounding area, because it is precisely this area that makes the site’s universal nature possible.

Suscríbete a nuestra newsletter

y recibe el mejor contenido de i+Descubre directo a tu email